Professional Guidelines for Interpreting in Educational Settings (First Edition)

Preface

The National Association of Interpreters in Education (NAIE)’s overarching mission is to empower interpreters working in educational settings, to bring forth and promote best practices in educational interpreting, and to enhance the educational outcomes of d/Deaf, hard of hearing, and deafblind students. The information provided in this publication, Professional Guidelines for Interpreting in Educational Settings, creates a framework that broadly reflects the quality of services required to support students in accordance with their Individualized Education Programs. This publication is the first edition of a national effort to identify educational interpreting standards and appropriate considerations for interpreter qualifications, roles, responsibilities, ethical conduct, and appropriate hiring practices.

These Guidelines support local and state education agencies, educational interpreters, parents, and other essential stakeholders in establishing and implementing best practices in educational interpreting. Professional excellence is based on standards of competency that align with ethical practices, promoting fundamental obligations and assurances to consumers. While we recognize that states and local education agencies have unique needs, an overarching purpose of these Guidelines is to establish minimal levels of standardization, as is expected within all professions. Legal considerations at the state and national level will take precedence, and there will undoubtedly be situations to which special considerations must be given. Such is the nature of working within Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004). Likewise, these Guidelines can be expected to expand and adapt alongside new solutions and challenges that will emerge within the field.

Conventions and Scope of Document

The NAIE recognizes and embraces the vast range of hearing losses, communication modalities, and cultural identities among students who utilize interpreters in educational settings. Within these guidelines, the term deaf has been utilized to collectively denote students who are deaf, Deaf, hard of hearing, hearing-impaired, and deafblind.

While NAIE recognizes the classification of captioning, transcription, cued language, and oral interpretation/transliteration as educational interpreting services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, the scope of the current document primarily applies to the provision of sign language interpreting in educational settings. While it is best practice to utilize educational interpreter as the official title of employment, the NAIE asserts that these Standards and Guidelines apply to each individual who provides any type of interpreting in an educational setting, regardless of official job title. As such, the term educational interpreter has been utilized to refer to all individuals providing sign language interpreting services in educational settings.

Children and youth are entitled to interpreting services across multiple educational settings. For the purposes of this document, the term school has been utilized to collectively address various types of educational entities and settings that may exist.

Acknowledgments

NAIE gratefully recognizes all those that have contributed their expertise and guidance in the development of this publication. Particularly, NAIE would like to acknowledge the University of Northern Colorado, Department of ASL and Interpreting Studies, for supporting the initial research regarding patterns of practice of educational interpreters under a U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education grant (2010- 2014; H325k100234). While these Guidelines are based significantly on the results of those projects, these Guidelines are solely the responsibility of the National Association of Interpreters in Education.

Writing Team

Susan E. Brown

President, NAIE Board of Directors

Faculty, University of Northern Colorado, Department of ASL & Interpreting Studies

Kristen Guynes

Publications Director, NAIE

Board of Directors

Faculty, Florida State University, School of Communication Science and Disorders

Jeremy Tuttle

Publications Director, NAIE

Board of Directors (2016-2018)

Educational Interpreter, Arizona School for the Deaf and the Blind

Contributors

Joelynne Ball

State Interpreter Education Coordinator, Idaho Educational Services for the Deaf and the Blind

Frances Beaurivage

Child Language Curriculum Specialist, Retired

EIPA Center Manager, Boys Town National Research Hospital

Colorado Department of Education

Educational Interpreter Advisory Committee

Tracey Frederick

Lead Educational Interpreter, Morrison Center

Emily Girardin

Faculty, University of Northern Colorado, Department of American Sign Language and Interpreting Studies – Co-Chair, RID IEIS Member Section

Becky Hillegass

Interpreter Specialist, Region 2 Grant

Coordinator, Virginia Beach City Public Schools

Sue Ann Houser

Educational Consultant, Pennsylvania Training and Technical Assistance Network

Emily Hume

Graduate Assistant, Florida State University School of Communication Science and Disorders

Kimberly Hutter

Texas Education Agency, National Leadership Consortium in Sensory Disabilities – Vice President, NAIE Board of Directors

Leilani J. Johnson

Director Emerita and Principal Investigator, University of Northern Colorado, Department of ASL and Interpreting Studies

Elizabeth Ann Monn

Teacher of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing

Carroll County Public Schools

Pennsylvania Educational Resources for Children with Hearing Loss Advisory Committee

Rachael Ragin

Teacher, Durham, North Carolina Public Schools

Barbara Raimondo

Executive Director, Conference of Educational Administrators of Schools and Programs for the Deaf

Jenna Schellenberger

Educational Interpreter, Edmonds, Washington School District, Deaf and Hard of Hearing Program

Carol Schweitzer

Retired Consultant for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Programs and Educational Interpreter Services, Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction

Sean Virnig

Associate Director, California Department of Education, State Special Schools and Services Division

Introduction

Within the field of interpreting, it is widely acknowledged that interpreting for children and youth in educational settings is vastly different from interpreting for adults and in community settings. To date however, little guidance has been available regarding how these differences are appropriately addressed. The mission of the National Association of Interpreters in Educational Settings (NAIE) is to fulfill a pivotal role in providing such guidance through leadership in addressing the unique and challenging complexities of educational interpreting. These foundational Guidelines for Interpreting in Educational Settings and accompanying Standards of Professional Practice, as put forth below, are essential to ensuring professional accountability and the provision of quality educational interpreting services for deaf students. These Standards and Guidelines are the culmination of contributions from various stakeholders who adamantly share the vision of improved student outcomes, including our many predecessors who have called for the improved professionalization of educational interpreting.

Decades of research have indicated a state of confusion among stakeholders regarding what appropriate and quality educational interpreting entails. Continued research, alongside the development of guidelines and supportive tools, have consistently been acknowledged as essential first steps in addressing the concerns of interpreted education (Antia & Kreimeyer, 2001; Commission on Education of the Deaf, 1988; Dahl & Wilcox, 1990; Hayes, 1991; Johnson, Taylor, Schick, Brown, & Bolster, 2018; Jones, Clark, & Soltz, 1997; Langer, 2004; Patrie & Taylor, 2008; Smith, 2016; Schick, 2007; Stuckless,1989). To meet the unique interpreting needs of children and youth with developing language, the NAIE asserts that educational interpreters possess specialized educational training and professional credentials. The Standards of Professional Practice outline minimal acceptable levels of knowledge, skills, and experiences which designate an educational interpreter as professionally qualified. The responsibility of upholding such expectations falls upon all stakeholders of interpreted education, including state and local education agencies, district and school-level administration, and individual practitioners.

While the NAIE acknowledges that the majority of states have established their own requirements for educational interpreters, the lack of national standardization has left hiring educational entities, interpreter education/training programs, and educational interpreters without clear direction regarding the requisite skills and knowledge needed to provide quality, appropriate, and legally-compliant educational interpreting services. Therefore, as the field moves towards such standardization, a gap between the credentials of the current workforce and those entering the field adhering to these pivotal expectations is inevitable. NAIE will continue to work with state and local agencies in facilitating support to improve the credentials of the current workforce, with the provision of quality interpreting services remaining paramount.

NAIE emphasizes that the provision of quality and effective interpreting services in educational settings is enforced by several federal laws. The overarching Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) mandates that effective communication, including the provision of interpreting services, be provided for deaf and hard of hearing individuals at all publicly accessible places and events. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act specifically addresses the need for communication access in outlawing discrimination against, and the exclusion of, deaf and hard of hearing individuals. Most specific to educational settings, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004) mandates educational accessibility through signed communication, and designates educational interpreters as related service providers (Sec. 300.34a) who must be qualified in the provision of their professional services.

While it is not the stance of NAIE that educational interpreting is an appropriate service for all deaf students, the scope of this document assumes that the need for such services has been determined through professional and legally-compliant decision-making. Specific procedures for prescribing educational interpreting services under IDEA mandate an official IEP team meeting, in which all stakeholders, including a teacher of the deaf and qualified educational interpreter, have the opportunity to provide professional recommendations. Present levels of performance and individualized considerations must be explored in domains such as, but not limited to, language, communication, academic, and social/functional skills. Secondarily, as a federallydefined related service, the determination to provide educational interpreting services must be accompanied by the development of specific measurable educational goals to which the educational interpreting services can contribute.

We would be remiss not to address ongoing concerns regarding appropriate educational placement and programming for deaf students. The nature of an interpreted education, the likelihood of inequitable access, and the benefit of direct, rather than interpreted, communication for students with language delays have been expressed (Schick, 2007; Wolbers, Dimling, Lawson, & Golos, 2012). In typical situations, language acquisition is a natural process that results from direct, scaffolded, and incidental interaction with proficient language models (Kurz, 2004; Monikowski, 2004; Schick, 2007; Winston, 2004; Wolbers, et al., 2012). Because the overwhelming majority of deaf children are born to hearing parents, who are not typically proficient in American Sign Language (ASL), the type of language-rich interaction required to provide natural acquisition of ASL is often not available.

Consequently, many deaf students demonstrate spoken and/or sign language delays that require intensive intervention beyond the scope of educational interpreting (Lawson, 2012; Lederberg, Schick, Spencer, 2013; Public Policy Associates, 2006; Smith, Wolbers, & Cihak, 2015). Like all languages, students who will potentially use ASL must develop a foundation of the language prior to using it for communication and learning purposes (Monikowski, 2004; Patrie & Taylor, 2008; Schick, 2004; 2008). In such cases, interpreting the language of the classroom, which is aimed towards hearing students with typical language development, is unlikely to provide educational access as intended (Monikowski, 2004; Schick, 2004; Winston, 2004). Therefore, an educational professional proficient in sign language who can facilitate language directly may be more appropriate (Schick, 2007; 2008; Smith, Wolbers, & Cihak, 2015). The potential contributions of qualified native signers and deaf professionals to serve as natural language models should be strongly considered. Students with the most significant language delays require the most experienced educational professionals. Therefore, professionals tasked with overseeing language facilitation for deaf students must possess the education, training, and credentials to do so. The NAIE emphasizes that a qualified educational interpreter, having met the standards as put forth, can contribute to discussions regarding a student’s readiness to utilize educational interpreting services.

Section I: Standards of Professional Practice

STANDARD I: ACADEMIC CREDENTIALS

An educational interpreter has completed an accredited four-year interpreter education program; with specialized training in the field of educational interpreting. At a minimum, a qualified educational interpreter has:

- Successfully completed a four-year degree in interpreting and has demonstrated knowledge in the areas of:

- Educational theory

- Child and language development

- Roles and responsibilities in the educational environment

- Ethical and professional practices within an educational setting

- State and federal laws related to special education and deaf education

- Completed a supervised internship or practicum placement in an educational setting

STANDARD II: PROFESSIONAL CREDENTIALS

An educational interpreter has demonstrated professional knowledge and skill competencies. At a minimum, a qualified educational interpreter has:

- Achieved at least a 4.0 on the Educational Interpreter Performance Assessment (EIPA)

- Earned a passing score on the EIPA Written Test

STANDARD III: CONTINUING EDUCATION

An educational interpreter seeks out professional development opportunities that are relevant to the interpreting process, educational system, educational law, and current best practices. At a minimum, a qualified educational interpreter consistently:

- Develops and enhances both signing and interpreting skills through participation in professional training that builds upon current knowledge and skill competencies

- Accepts responsibility for developing and maintaining a relevant professional development plan, seeking a qualified mentor as necessary

- Meets professional development requirements as outlined by applicable state and/or local education agencies

STANDARD IV: SUPERVISION & ACCOUNTABILITY

An educational interpreter is supervised and evaluated by an interpreter who is trained in evaluating interpreting skills and is knowledgeable regarding best practices for interpreting in educational settings. At a minimum, a qualified educational interpreter:

- Is accountable for providing quality interpreting services under the supervision of applicable state and/or local education agencies

- Advocates for colleagues while holding the educational systems responsible for appropriate supervision

- Seeks out mentoring and professional development opportunities in response to appropriate feedback provided by qualified supervisors

Section II: Scope of Professional Practice

Professional and Ethical Practices

As professionals, interpreters are guided by principles and ethical practices that respect and protect the rights of the individuals with whom they work. Interpreting in educational settings presents unique considerations, as children and youth are developing individuals, rather than autonomous adults. The Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf/National Association of the Deaf Code of Professional Conduct is the overarching set of guidelines for sign language interpreters across multiple domains. More specific guidance related to educational settings has been provided by the Educational Interpreter Performance Assessment (EIPA) Guidelines for Professional Conduct (Schick, 2007). The purpose of these Guidelines is to extend such guidance by articulating best practices across a variety of domains. Whether employed directly by the school or contracted through an external agency, educational interpreters are bound to specific regulations at the federal, state, and school levels. Educational interpreters must be knowledgeable about each set of applicable guidelines to appropriately draw upon them in professional decision-making.

Confidentality

Educational employees are prevented from sharing information beyond a relevant and need-to-know basis, as mandated by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA), which protects the privacy rights of students. Upholding confidentiality is an essential cornerstone of the interpreting profession, ensuring that consumers are protected and professional relationships are maintained. The emphasis of confidentiality within the profession, however, should not be misconstrued as exempting educational interpreters from their duties as legally-mandated reporters, which apply even when information has been obtained while interpreting. All school personnel, including educational interpreters, are required to immediately report any suspected abuse or illegal activity to the appropriate authorities. Likewise, pertinent student-related information, such as academic performance, family situations, and behavioral concerns, should be shared within the relevant educational team for the purposes of addressing student needs and facilitating positive outcomes.

Appropriate Language and Modality

There are several variations of sign language that may be used in educational settings. American Sign Language (ASL) is the unique language of the Deaf community in the United States and parts of Canada, while other signing systems are influenced by English. Signed English systems may include those such as Signed Exact English, Seeing Essential English, and Conceptually Accurate Signed English. Visual Phonics, Morphemic Sign Language, and Cued Language are systems that incorporate visual representations of sounds. It is absolutely essential that students have access to at least one complete linguistic system for communication and learning purposes. Decisions regarding the appropriate language must be collaboratively determined by the educational team, with utmost respect for personal and familial preferences. Particularly in the case of students receiving services under IEPs, decisions and considerations regarding communication must be formally considered and documented.

Section III: Educational Interpreter Roles and Responsiblities

Defining Roles versus Responsibilities

Although often used interchangeably, within the scope of these Guidelines, a role refers to a specific function of the educational interpreter while a responsibility refers to a specific task implemented within a role. Each role and responsibility can be direct or indirect. Examples of roles that educational interpreters may fulfill include interpreter, language model, language facilitator, and tutor, among others. Examples of responsibilities within those roles can include interpreting, supporting language attempts, encouraging appropriate interaction, and pre-teaching vocabulary. The entire educational team is collectively responsible for determining and documenting the appropriate roles and responsibilities of each educational interpreter.

Facilitation of Student Independence

While the primary purpose of educational interpreting services is to facilitate communication access, related roles and responsibilities are often appropriate. It is not uncommon for students who are young in age, delayed in development, or unfamiliar with interpreting services to require additional support directly from the educational interpreter. Because educational interpreters serve as language-accessible adult role models, appropriate roles and responsibilities can potentially be far-reaching. It is important to emphasize, however, that this should not be misconstrued to indicate that educational interpreters can fulfill roles or take on responsibilities beyond the scope of their professional qualifications. Direct support can only be appropriately assigned when the facilitation of student independence remains at the forefront of discussion. Across all domains, educational interpreters are expected to foster independence by reducing the level of extraneous support provided as students mature, preparing them towards becoming autonomous consumers of interpreting services as adults.

Emergency Protocols

Alongside other educational professionals and adult staff members, educational interpreters must be trained in the emergency protocols of the school and expected to immediately address the serious or emergency concerns of any student. Accessible adaptations, such as the use of text messaging, should be considered for deaf students without complete access to auditory alerts and information. Visual accessibility of information during emergency situations is particularly essential and should be discussed and determined by the educational team preemptively, with a clear meeting spot established in the case that the educational interpreter and student are separated during an emergency drill or situation.

Supporting Other Professionals

The expertise of educational interpreters can extend beyond educational team planning, through the provision of professional development opportunities for administration, general education teachers, and supportive staff. Collaborative preparation and information-sharing regarding topics such as the implications of hearing loss, specific educational needs of students, and considerations for interpreted education can be particularly beneficial when deaf students are entering new classrooms at the beginning of the school year or new semester.

Supporting Other Professionals

Educational interpreters often serve as sign language models for the students with whom they work. An inherent component of interpreting is presenting the content and intent of the spoken message at a language level most readily understood by the deaf individual. Because of the developing nature of children and youth in educational settings, it is appropriate to provide additional support to facilitate emerging and developing language such as repeating, clarifying, or restructuring information. In doing so, educational interpreters may need to interact directly with the student for the purposes of monitoring comprehension and making appropriate adjustments. Strategies that support language development beyond interpretation must be guided by educational professionals, such as speechlanguage pathologists and teachers of the deaf, who possess expertise in the language being utilized and credentials in language development.

Supporting the School Environment

As educational professionals, educational interpreters may be expected to support the general safety, productiveness, and operations of the school. When interpreters are required to fulfill such duties that are unrelated to interpreting, they must be within the boundaries of the compensated working hours and agreed upon job description. Special consideration must also be given to ascertain that these responsibilities do not have the potential to interfere with the need for educational interpreting services, as students are entitled to consistent educational access, including before and after the instructional day. For example, if all educational professionals are assigned responsibilities for assisting with student supervision before school, alternative arrangements must be made regarding the potential need for interpreting services at that time.

Facilitating Social Interaction and Teaching Sign Language

Age-appropriate social interaction with peers and adults is an essential component of the educational experience. For deaf students however, such interaction presents challenges which may require support. Educational interpreters can help facilitate social development by supporting students’ conversational attempts and informally teaching conversational sign language to teachers, staff, and peers. Educational interpreters may also support informal sign language activities such as studentled clubs. However, the provision of formal ASL instruction, whether for credit or community-based, requires teaching credentials that typically extend beyond educational interpreters’ expected qualifications.

Behavior Management

Clear procedures for addressing student behavior are essential to any classroom management plan. In each classroom, the teacher is responsible for establishing such procedures and reinforcing them with students. Teachers also take the lead on determining the extent to which other adults in the classroom, such as volunteers, paraprofessionals, and professional related service providers will assist in implementation. The educational team must consider the age, academic level, developmental level, and maturity of students in determining the level of support that the interpreter will provide. However, an educational interpreter cannot be expected to routinely provide direct correction of students’ behavior. An interpreter becoming too involved in the behavior management of deaf students will interfere with the ability to maintain a professional relationship and skew the perception of an interpreter’s role. Attempting to manage the behavior of any student while actively interpreting will impact the quality and clarity of the interpreted message. Educational interpreters should not be expected to supervise classrooms, which can also compromise students’ perspectives regarding appropriate roles of the professionals in the classroom.

Tutoring

Educational interpreters are uniquely positioned to communicate directly with deaf students in their language, thus, are often an appropriate choice to provide direct tutoring services. Appropriate tutoring includes preliminary exposure to content-specific vocabulary, reviewing essential concepts, and/or providing additional opportunities for guided practice. Tutoring should not be used to replace instruction, nor should it occur during active interpretation in the classroom. Educational interpreters should not be expected to independently determine materials, assignments, or goals. Decisions regarding tutoring should be based on individual student needs and the qualifications of the educational interpreter. Appropriate training and qualifications must be in place prior to the implementation of tutoring services.

Supportive Hearing Assistive Technology

Hearing assistive technology, such as hearing aids, cochlear implants, and frequency-modulated (FM) systems, has become an integral component of many deaf students’ educational programming. Alongside other educational team members, educational interpreters are expected to be knowledgeable about the hearing technology used by the students with whom they work. At a minimum, educational interpreters should be able to understand the expected level of auditory access and recognize signs of concerns. As determined by the educational team, and with guidance, it may be appropriate for an educational interpreter to fulfil more specific roles related to audiological equipment.

Section IV: Interpreting-Related Considerations

Considerations Specific to Educational Interpreting

Beyond the foundational considerations applicable to sign language interpreters across various settings, unique considerations exist related to interpretation in educational settings. Primary guiding factors include the nature of developing children and the adherence to federal, state, and local regulations.

Interpreting Assessments

In any assessment situation, the appropriateness of sign language interpretation must be given significant consideration. Caution must be taken to ensure that the use of sign language, whether direct or interpreted, does not inadvertently skew the results of the specific skills or knowledge being assessed. Most formal and informal assessments are not normed for deaf students nor designed for the use of sign language. Allowable accommodations and how they impact assessment results are determined differently for each assessment situation. It is essential that the entire educational team clearly understand an assessment’s protocols along with local and state education agency regulations for the use of sign language. Such guidelines must be thoroughly reviewed to determine which types of accommodations and modifications are allowable, the educational interpreter’s responsibilities in the process, and to what extent the materials can be accessed prior to testing for preparation purposes. Decisions regarding accommodations and modifications must be clearly documented and implemented exactly as such. In all situations, accommodations and modifications utilized for standardized assessments must align with those implemented throughout the school year.

Interpreting Extracurricular Activities

Educational entities regularly offer school-affiliated events that occur outside of the classroom and/or beyond the traditional school day. Examples include assemblies, athletic events, clubs, field trips, school performances, student government, social events, graduation ceremonies, and other special programs. Even when not academically-focused, these types of activities are essential components of holistic educational programming and must be made accessible to all students. The provision of effective communication for deaf and hard of hearing individuals, including but not limited to quality interpreting services, is mandated by several federal laws. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act ensures that students with disabilities have uninhibited access to all aspects of the educational experience, including those listed above. Additionally, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act mandates that individuals with disabilities not be discriminated against by way of exclusion in schools, jobs, and community events, specifically addressing the need for communication access. Finally, the Americans with Disabilities Act mandates effective communication for Deaf and hard of hearing individuals, including the provision of interpreting services, at publicly accessible places and events. The legal responsibility of each educational entity to provide interpreting services across all situations in the educational setting is clear.

Particular attention should be given to ensure that all stakeholders are involved in collaborative preparation for effective interpretation of such events. When a student requires interpreting services outside of the classroom, it is usually appropriate for the educational interpreter who is typically with the student to interpret the activity or event. However, consideration must be given to the nature, content, and duration of the event to ensure that an effective interpretation will be provided. When interpreting services are required beyond an educational interpreter’s contracted work schedule, such as after school, additional arrangements must be made. Educational interpreters cannot be expected to volunteer their professional interpreting services without compensation. The educational entity should establish an hourly rate schedule that is mutually agreed upon. Additional considerations should include hourly minimums and compensation for travel, as well as timelines and protocols for cancellation.

Interpreting Medical, Legal, and Sensitive Situations

Educational interpreters possess expertise unique to educational settings. Other interpreting situations, particularly those of a legal or medical nature, require specialized knowledge, skill sets, and credentials. Likewise, the nature of interpreting for adults requires a different expertise than interpreting for children, and national certification through the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf is expected.

Legal situations which an interpreter with specialized credentials is required include:

- Involvement of a child welfare and protection agency

- Statements made by the student could be used in future legal proceedings

- Potential suspension or expulsion

- Accusation of truancy, juvenile delinquency, or criminal activity

- Student is a witness, victim, or suspect

- Student is being escorted off campus

When these types of interpreting situations arise in a school setting, the educational entity is responsible for providing appropriate and legally compliant interpreting services. However, it cannot be assumed that an educational interpreter is inherently qualified to fulfill them, and contracting from outside the school is often required. State regulations, specific interpreter qualifications, and the nature of the situation must be carefully considered. Situations also exist in which it is not appropriate for an interpreter to be privy to certain information. For example, if a deaf student, parent, or employee wishes to discuss concerns regarding an educational interpreter, a neutral interpreter should be assigned to interpret that conversation. Likewise, it would be inappropriate for an educational interpreter to interpret sensitive and/or personnel-related meetings involving colleagues. If a student requires mental health or personal counseling services during the school day, it may be more appropriate to assign an interpreter other than the primary classroom interpreter. As well, an educational interpreter cannot be expected to fulfill conflicting roles, such as interpreting and participating simultaneously in an IEP meeting.

Section V: Preparation and Provisions

Preparing to Interpret

Preparation is an essential component of effective service delivery for all professionals, and educational interpreting is no exception. In educational settings, one of the most significant responsibilities of the interpreter is to present the classroom teacher’s instructional content in a way that is accessible to the student. Unlike other interpreting settings in which the responsibility to monitor comprehension of the speaker’s message falls almost exclusively on the deaf adult, educational interpreters must ensure that the message is presented in an educationally appropriate manner. Specific considerations include the student’s academic and language levels alongside the teacher’s designated learning objectives. Preparation prior to interpretation is required to ensure that the interpretation aligns with such considerations.

Provision of Time and Materials

An interpreter’s expertise is the ability to provide a clear, accessible, and cohesive interpretation of information presented by someone else. A foundational understanding of the content and subject-specific terminology will result in a more effective interpretation. While classroom teachers tend to specialize in a specific subject or grade-level area, it is impossible to expect educational interpreters to possess content expertise across the diverse range of topics and settings to which they may be assigned.

Compensated time to prepare for interpretation in a manner similar to that provided to other educational professionals is pivotal to this end. Curricular materials such as textbooks, student materials, lesson plans, and media should be consistently accessible to preview. Specific to extracurricular events, procedures should be in place to ensure that educational interpreters are provided information and materials for preparation in advance. Opportunities for educational interpreters to discuss upcoming topics and situations of interpreting with teachers and other service providers are also imperative.

Conductive Environmental Settings

Particularly due to its visual nature, effective educational interpreting requires attention to placement of the student, teacher, interpreter, and instructional tools. The educational interpreter and student should have consistent access to areas of the classroom from which interpretation can be appropriately provided. These placements should allow the educational interpreter to remain in the student’s line of sight, be in close proximity to the speaker, unobstructed, and well-lit. To ensure the simultaneous accessibility of the speaker and educational interpreter, it is often necessary for the educational interpreter to change placements frequently by shadowing the speaker(s).

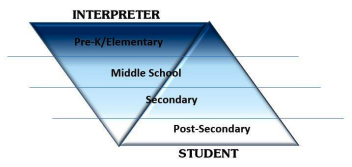

An educational interpreter’s relative distance from the teacher and the student depend on the student’s age, maturity level, setting, and personal preferences. For example, an educational interpreter in a preschool classroom may be comfortable sitting on the floor among the students during circle time while an interpreter in an elementary classroom may sit amongst a group during collaborative work. An educational interpreter in a high school classroom, however, might be better situated at a further distance from the student, such as seated or standing at the front of the classroom.

Appropriate Supervision and Evaluation

Performance evaluations are key components of any effective accountability system for professionals. Likewise, educational interpreters must be periodically evaluated regarding both their interpreting skills and professional practices. It is essential that interpreter evaluators possess advanced credentials and expertise in the assessment of educational interpreting. Evaluators should be able to articulate specific strengths and suggestions for improvement to the interpreter being evaluated. Because many administrators do not possess such expertise, it is often necessary to collaborate with a lead interpreter or professional from outside the district. However, the role of school administration in overseeing educational interpreters’ professionalism and adherence to school policies is also essential and should not be exempted.

Team Interpreting

The complexities and challenges of educational interpreting cannot be overstated. Concerns regarding the ability of a single interpreter to provide complete educational accessibility have been expressed, despite the notion that this is the expectation of an interpreted education. Team interpreting is the strategic pairing of two professional interpreters to optimize effective interpretation in challenging situations, such as those which are intensive in content, duration, or delivery method.

Quality team interpreting should not be misconstrued as simply splitting an assignment between two interpreters. Rather, purposeful team interpreting requires both professionals to work together in the preparation, implementation, and debriefing to deliver more effective interpreting services. Examples of situations in which team interpreting can be particularly beneficial include length and complexity of content and extracurricular programs.

Inactive Interpreting Time

It is the nature of educational settings to ebb and flow in the intensity of content presented, thus, the intensity at which educational interpreters must process and interpret information from one language to another. Teacher-led direct instruction typically requires an educational interpreter to work most intently in processing and providing the message. The scheduling of routine pauses during intensive content delivery at approximately twenty-minute intervals and/or the use of team interpreting should be considered. Likewise, the susceptibility of deaf students to experience visual fatigue during these periods of instruction must also be considered.

As the classroom focus shifts to guided practice and eventually, independent work, the intensity at which the interpreter and student must process the interpreted message begins to decrease. These periods of inactive interpreting time, often referred to as down time, are essential for reducing the cognitive load and physical strain put onto the interpreter as well as the deaf student. However, as the grade level of the educational setting increases, these inherent opportunities for inactive interpreting tend to be less frequent, particularly in high school settings and at extracurricular events. Careful attention must be given to ensure that an unreasonable burden of language processing is not put on the interpreter, which will have a negative impact on the effectiveness of interpreting services.

Professional Development and Mentoring

Educational interpreters are responsible for continuously developing their knowledge and skills in a manner similar to other educational professionals. Individualized professional development plans for educational interpreters should align with current levels of skills and knowledge while considering specific implications related to the current educational placement. Staying abreast of evidence-based and best practices related to educational interpreting is essential through the attendance of conferences and participation in training. Collaboration with educational interpreter colleagues is an inherent component of professionalism. Depending on the relevant expertise and professional aspirations, a mentor-mentee relationship can also be established. While educational interpreters can benefit significantly from the expertise of professional interpreters and educational colleagues with other specializations, it is also critical that they have consistent access to more experienced educational interpreters and native sign language users to assist in professional growth. In establishing formal mentoring relationships, appropriate training and oversight should be provided. Qualified mentors possess expertise in educational interpreting, have advanced knowledge of approaches to support sign language development, and have undergone training to accurately assess interpreting skills and provide effective feedback. Procedures for formal professional development plans, establishment of mentors, particularly for new educational interpreters, should align with those of other educational professionals within the educational entity. Likewise, the facilitation of professional development opportunities and compensated time to pursue them should also be provided.

Section VI: Considerations for Hiring Placement, and Promotion

Provision of Appropriate Educational Interpreting Services

Whether prescribed under IDEA, Section 504, or the ADA, educational interpreting services must align with the individualized educational needs of deaf students. It is important to hire qualified educational interpreters who are able and willing to meet the diverse and evolving needs of students. To secure qualified educational interpreters who can provide legally-compliant services, it is essential to develop an appropriate recruitment and hiring protocol. Such hiring procedures should align with current hiring practices for other educational professionals while also addressing the unique considerations for educational interpreting positions.

Summary of Minimum Standards

As demonstrated by the Standards of Professional Practice, the requisite credentials of professional qualifications include:

I: ACADEMIC CREDENTIALS

- Completion of a 4-year interpreting degree

- Specialized training in educational interpreting

II: PROFESSIONAL CREDENTIALS

- At least 4.0 on EIPA Performance

- Passed EIPA Written Test

III: CONTINUING EDUCATION

- Develops skills and knowledge

- Maintains professional development plan

- Adheres to state and local requirements

IV: SUPERVISION & ACCOUNTABILITY

- Provides qualified services

- Advocates for profession

- Seeks accountability

Salary and Benefits

Selecting a professional to join the educational system is a two-way process. Both parties must agree that the position is an appropriate match. Part of this process is the provision of a fair salary and benefits package. The hiring entity should work with the Human Resources department to develop a clear salary schedule and benefits package that will attract and retain qualified educational interpreters. The pay scale for the position of educational interpreter should align with the district’s pay scale and benefits offered to employees that hold similar academic credentials, certifications, and years of experience.

Providing Substitute Interpreters

When an assigned educational interpreter is unavailable, such as in the case of an absence, the school remains responsible for ensuring educational accessibility. As such, it is the educational entity’s responsibility to ensure that those providing educational interpreting services, including on a substitute basis, adhere to the Standards of Professional Practice.

To facilitate the most effective interpretation, essential information regarding student considerations and logistics of the school should be accessible. To ensure compliance and consistency, a specific staff member should be assigned to oversee the provision of substitute educational interpreters as needed, including the facilitation of required authorizations such as licensing, fingerprinting, and background checks.

Official Job Title

Educational Interpreter is the most appropriate and legally-compliant job title, as it recognizes the educational component of the position alongside the distinct interpreting skill set required. Job titles such as assistant, aide, language facilitator, and paraprofessional do not accurately reflect an educational interpreter’s distinctive qualifications and professional position, which can lead to misunderstandings regarding appropriate roles and responsibilities. Additionally, for the purposes of accountability and accurate representation of the services being provided, educational interpreter is the job title tracked at the federal and many state levels.

Designating a Lead Educational Interpreter position for a candidate with advanced expertise in educational interpreting alongside the credentials and experience to service in a supervisory role can assist with interpreter placement and scheduling, appropriate roles and responsibilities, mentoring, supervision, and evaluation, oversight of professional practices, professional development opportunities, and collaboration.

Educational Interpreter Placement

When interpreting services are required beyond the educational interpreter’s contracted working days and/or hours, additional compensation is necessitated. Like all professionals, educational interpreters should have opportunities for career advancement. Incentives should exist for educational interpreters to grow professionally through the completion of advanced degrees and credentials.

As professionals, educational interpreters are expected to adapt to a variety of settings and situations, while also pursuing specialized expertise in certain domains such as age and grade levels, content areas, communication modalities, and specialized student characteristics. Consideration should be given to ensure that educational interpreters are only placed with students for whom they can interpret effectively and address individualized needs. It is the joint responsibility of the hiring educational entity and the educational interpreter to ensure that there is an appropriate match between student needs and professional skill set. Specific considerations include, but are not limited to, the student’s educational placement, educational goals and objectives, preferred language modality, specific language levels, maturity, and readiness to use interpreting services.

Despite a common misconception that newer interpreters can be placed in settings with younger students, those who are young in age or developmental level require the most experienced educational interpreters. In many situations, it is not possible for one educational interpreter to meet the individualized needs of multiple students in one classroom, particularly when different language systems are required for communication.

Determining Expectations and Developing the Job Description

Prior to considering the logistics of the hiring process, determining appropriate expectations is essential. It is the responsibility of each educational agency to develop a clear job description for the position of an educational interpreter that aligns with national, state, and local regulations. An effective job description should first outline expectations of all educational professionals such as educational experiences, the willingness and ability to successfully complete a background investigation, language proficiency, and commitment to professionalism.

More specific to educational interpreting, at a minimum, the job description should include:

- A clearly defined job title of Educational Interpreter

- A job summary that clearly designates the primary role of interpreting, alongside supplementary roles and responsibilities, as applicable

- An overview of position-specific prerequisites, such as:

- Academic and professional credentials

- Proficiency in American Sign Language and/or other relevant signing systems

- Aptitude to work as a contributing member of the educational team

- Physical, mental, and emotional capableness for carrying out essential requirements of the position

- A clear description of the terms of employment, such as:

- Compensation and benefits

- Number of contractual working days o Hours per day worked

- Expectations for extracurricular events that fall outside of the contracted schedule

The educational interpreter applicant should complete all standardized interview processes in a manner similar to those conducted of other applicants for professional positions. In addition to personnel who routinely participate in such interviews, a fully qualified educational interpreter should participate as a member of the interviewing team.

References

Antia, S. D., & Kreimeyer, K. H. (2001). The role of interpreters in inclusive classrooms. American Annals of the Deaf, 146(4), 355-365.

Commission on Education of the Deaf. (1988). Looking to the Future: Commission on Education of the Deaf Recommendations. American Annals of the Deaf 133(2), 79-84. Gallaudet University Press. Retrieved January 26, 2019, from https://muse.jhu.edu/article/386780/pdf.

Dahl, C., & Wilcox, S. (1990). Preparing the educational interpreter: A survey of sign language interpreter training programs. American Annals of the Deaf, 135(4), 275-279.

Hayes, P. (1991). Educational interpreters for deaf students: Their responsibilities, problems, and concerns (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, 1991). Ann Arbor, MI: Proquest.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (2004). U.S. Department of Education: Promoting educational excellence for all Americans. Retrieved October 11, 2008, from Building the Legacy: IDEA: http://idea.ed.gov/explore/home

Johnson, L. J., Taylor, M. M., Schick, B., Brown, S., & Bolster, L. (2018). Complexities in educational interpreting: An investigation into patterns of practice. Edmonton, Alberta: Interpreting Consolidated.

Jones, B. E., Clark, G. M., & Soltz, D. F. (1997). Characteristics and practices of sign language interpreters in inclusive education programs. Exceptional Children, 63(2), 257-268.

Kurz, K. B. (2004). A comparison of deaf children’s comprehension in direction communication and interpreted education. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Kansas.

Langer, E. C. (2004). Perspectives on educational interpreting from educational anthropology and an internet discussion group. In E. A. Winston (Ed.), Educational interpreting: How it can succeed (pp. 91-112). Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

Lawson, H. R. (2012). Impact of interpreters filling multiple roles in mainstream classrooms on communication access for deaf students (Master’s thesis, University of Tennessee, 2012). Knoxville: University of Tennessee.

Lederberg, A. R., Schick, B., & Spencer, P. E. (2013). Language and literacy development of deaf and hard-of-hearing children: successes and challenges. Developmental psychology, 49(1), 15.

Monikowski, C. (2004). Language myths in interpreted education: First language, second language, what language? In E. A. Winston (Ed.), Educational interpreting: How it can succeed (pp. 48-60). Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

Patrie, C., & Taylor, M. (2008). Outcomes for graduates of baccalaureate interpreter preparation programs specializing in interpreting in K-12th grade settings. Rochester, NY: RIT Digital Library Printing.

Public Policy Associates, Incorporated. (2006). Supply and demand for interpreters for the deaf and hard of hearing in Michigan (Michigan, Department of Education). Retrieved from http://mi.gov/documents/cis/Interpreter_Supply_and_Demand_Final_Report_185252_7.pdf

Schick, B., & Williams, K. (2004). The educational interpreter performance assessment: Current structure and practices. Educational interpreting: How it can succeed, 186-205.

Schick, B. D. (2008). A model of learning within an interpreted k-12 educational setting. In P. C. Hauser (Author) & M. Marschark (Ed.), Deaf cognition: Foundations and outcomes (pp. 351-385). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schick, B. D. (2007, August 1). EIPA Guidelines of Professional Conduct for Educational Interpreters. Retrieved September 15, 2008, from: http://www.classroominterpreting.org/Interpreters/proguidelines/EIPA_guidelines.pdf

Smith, Kristen R. “Towards the Validation of the Educational Interpreter Roles and Responsibilities Guiding Checklist.” Texas Tech University, May 2016, ttu-ir.tdl.org/ttuir/handle/2346/67143.

Smith, K. R., Wolbers, K. A., & Cihak, D. F. (2015). Effects of language intervention versus traditional interpretation for a deaf preschool child: A pilot study. Communication Disorders, Deaf Studies, & Hearing Aids, 3(4), 1-10. doi:10.4172/2375-4427.1000141

Stuckless, E. R. (1989). Educational Interpreting for Deaf Students: Report of the National Task Force on Educational Interpreting.

Winston, E. A. (2004). Introduction. In E. A. Winston (Ed.), Educational interpreting: How it can succeed (pp. 1-6). Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

Wolbers, K. A., Dimling, L. M., Lawson, H. R., & Golos, D. B. (2012). Parallel and divergent interpreting in an elementary classroom. American Annals of the Deaf, 157(1), 48-65.

Guidelines Presentation

We are excited to share with you a summary of key points from the Professional Standards and Guidelines for Interpreting in Educational Settings, which were released in January, 2019. This self-paced presentation outlines the overarching components of the Guidelines and rationale for their inclusion that you can use to inform your own practice and/or share with other stakeholders. You can view this presentation here: Summary of Professional Standards and Guidelines

FAQ’s

Since the release of the Guidelines, the NAIE has fielded numerous questions and concerns from various stakeholders. Therefore, we’ve outlined some of the most common inquiries in this Guidelines FAQ to provide an avenue for official guidance from the NAIE. This document will be periodically updated as new topics emerge. You can view the FAQ here: Guidelines FAQ

This document may be cited as:

National Association of Interpreters in Education. (2019). Professional Guidelines for Interpreting in Educational Settings (1st ed.). Retrieved from www.naiedu.org/guidelines.

© 2020 National Association of Interpreters in Education